March 11, 2019

By Janna Goudarzi, CPA | Nonprofit Tax Manager

All 50 states have unclaimed property laws (also known as escheat laws) that require organizations to make reasonable efforts to contact those to whom they owe money or property and then remit any unpaid items to the state. These rules generally apply to all entities, including exempt organizations. If an organization is unable to locate the property owner, it must remit the unclaimed property to the appropriate state for the state to then assume the responsibility of trying to pay the funds to the true owner. As discussed below, organizations that do not monitor and properly remit unclaimed property can face significant liabilities if audited by the states. We’ve seen an uptick in state audits and inquiries of nonprofit organizations and provide the following reminders for your consideration.

Types of Unclaimed Property

Unclaimed property is intangible or tangible property held in your custody that belongs to someone else. This definition is broad and includes a wide range of types of property. Generally, in business settings the most common types of property are uncashed payroll checks, uncashed vendor checks and customer overpayments. In some industries unclaimed property may also include savings or checking accounts, stocks, uncashed dividends checks, refunds, traveler’s checks, trust distributions, unredeemed money orders or gift certificates (in some states), insurance payments or refunds, life insurance policies, annuities, certificates of deposit, customer overpayments, utility security deposits, mineral royalty payments, and contents of safe deposit boxes.

State Escheatment Laws

Unclaimed property becomes “abandoned” if the organization has no contact with the owner over a certain period of time specified in law. Each state has a different period in which funds must be remitted, and different periods for different types of property, but generally 1 to 5 years after contact with the owner has been lost (the dormancy period). Under state escheatment laws, organizations are responsible for first making attempts to locate the owner and remit the property to the owner, and then reporting and surrendering “abandoned” funds to the proper state agency (e.g. in Maryland to the Comptroller’s Office). The asset is to be remitted to the state of the true owner’s last known address, and if that is not known, to the holding business’s state of incorporation. The state will then attempt to locate the owners and return the assets. There is no statute of limitations period for the owner to file a claim and receive the funds that the state is holding.

Unclaimed property audits are a source of revenue for the states. They routinely conduct audits and assessments of unclaimed property and can assess penalties and interest for non-compliance. Most states have no statute of limitations for doing audits and assessments for unclaimed property. Additionally, some states request an organization go back as far as 10 years to do a “self-audit” for any unclaimed property and make any unpaid remittances to the state. When organizations do not have proper policies and procedures in place to comply with the unclaimed property laws, state auditors may use extrapolation and estimation techniques to determine the liability amount. This can be a large, unplanned expense for an organization.

To avoid a possible audit assessment that usually includes interest and penalties, the organization can initiate its own self-audit and apply for a voluntary disclosure agreement with the state in order to remit the unclaimed property amounts but avoid the typical state audit penalties.

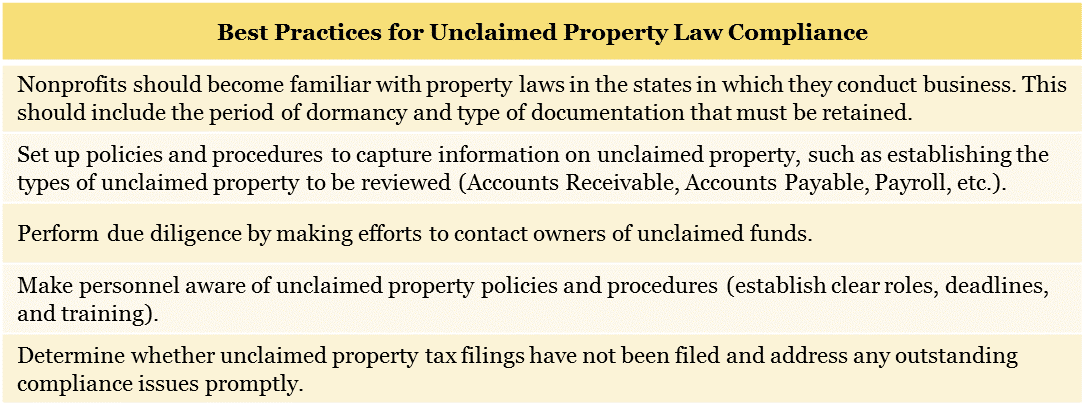

Best Practices for Nonprofits

To avoid potential liabilities, an organization should establish policies and procedures to deal with unclaimed property and ensure that all unclaimed property filings are completed in a timely manner. The organization should at least annually review and document reasons why checks were voided (e.g., it was written in error and replaced), review old receivable and payable balances, deferred income accounts, overpayments, and any suspended accounts. Keep this documentation for use in case of an audit. And never ever revert uncashed items into income unless it is known that the item was an error and isn’t unclaimed property that is owed to the owner or to the state.

As with many areas of accounting, following formal, documented policies and procedures is the key to compliance. For additional information on unclaimed property, including guidance for responding to a state notice, please contact Richard J. Locastro, CPA, JD at rlocastro@grfcpa.com or 301-951-9090.